Methods of Primary Data Collection in Research Methodology

Master the top methods of primary data collection in research methodology. Learn to use surveys, interviews, and experiments to gather original, high-quality data.

Emilia

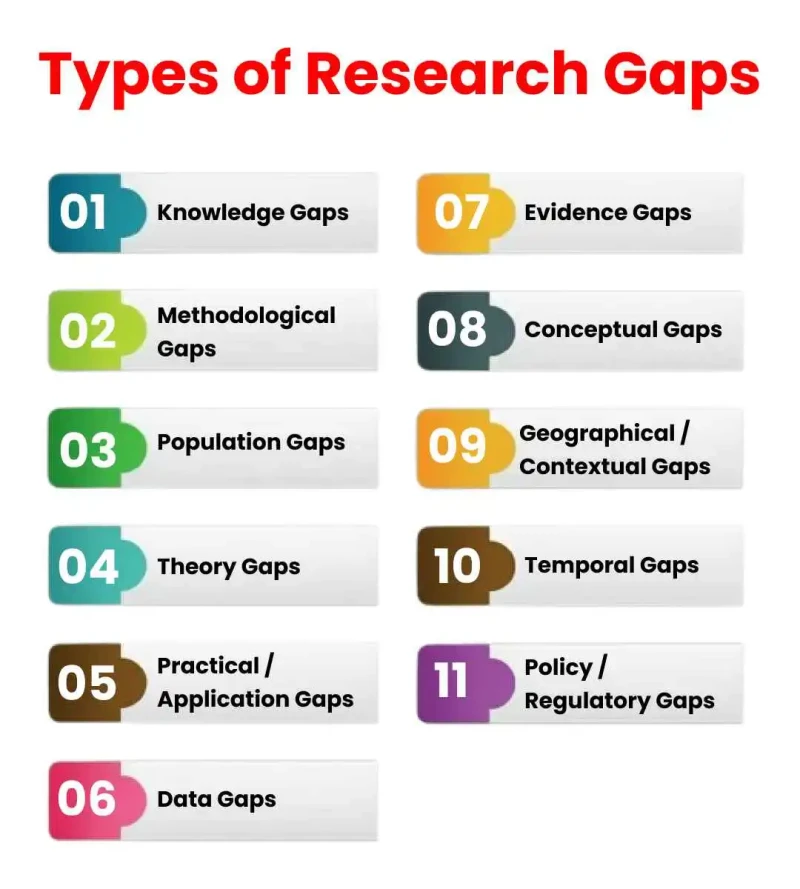

All successful studies begin with the identification of research gaps, those places in your discipline where there is a lack of knowledge, conflicting knowledge, or unfinished knowledge.

Identifying those gaps allows researchers, students and professionals to concentrate on questions that are significant, creating studies that are fresh, relevant and grounded in a strong research methodology. By aligning their objectives with these appropriate methods, scholars can ensure that their investigations address meaningful questions which follow a systematic and credible approach.

Researchers identify these gaps to ensure their publications, dissertations, and theses achieve a high standard of quality. In this blog, we will explore research gaps, effective strategies for identifying them, and methods to prioritise the most relevant gaps for your study.

A research gap is an important aspect of a field that has not yet been sufficiently explored. It is distinct from an unresolved minor question, which can be inconsequential or too specific to provide much understanding.

Research gaps are helpful because they:

Pinpoint possible areas for innovative and novel research.

Prevent duplication by ensuring your research builds upon, rather than replicating, prior research.

Provide direction to researchers in developing research questions that advance the field.

Expressing a clear research gap in your research proves attentiveness to existing literature and highlights your value in building new knowledge.

When writing a research gap, it is crucial to clearly articulate the gap, explain why it matters, and show how your study will address it. A well-defined research gap not only strengthens your work but also positions it as a valuable contribution to the academic community.

It occurs when there is a lack of information on a topic. They are required in research that aims to broaden knowledge.

Example: Few studies on employee creativity impacted by hybrid workplaces.

The research on the influence of hybrid workspaces on worker innovation and teamwork is still inadequately investigated. Differences in remote and in-office schedules, team dynamics, and management styles bring uncertainty. Knowledge of these factors can assist organisations in creating policies that will stimulate innovation, worker participation, and productivity and integrate flexible work arrangements.

Arise when earlier studies employed outdated or inadequate methods. They help to improve research design.

Example: Experimental or longitudinal designs can be used to enhance online learning outcomes surveys.

Most studies which are on longitudinal designs are based on simple surveys that could miss the long-term trends or cause-and-effect relationships. Longitudinal or experimental approaches can yield more consistent, reliable, and generalizable data. Refreshing research designs makes it possible for findings to properly capture the changing nature of online learning and over-time effectiveness.

It occurs when some demographic groups are not well-represented. A key requirement for representative studies.

Example: Mental health studies of adults without including teenagers or minorities.

Studies on mental health tend to concentrate on a specific adult population, excluding teenagers or minorities. This exclusion makes the findings less applicable and could miss out on distinct stressors or requirements. Having varied populations promotes more inclusive, fair, and applicable findings for mental health interventions in a wide range of populations.

Arise when existing models fail to account for phenomena to their entirety. Useful in theory development or refinement.

Example: Failure of models to account for youth digital addiction behaviour.

Existing behavioural research theories are unable to encapsulate the nuances of digital addiction among young people. Social, psychological, and environmental determinants tend to be insufficiently captured. Bridging this gap can result in more sophisticated theories and improved interventions, helping teachers, parents, and policymakers reduce youth digital dependency.

Arise when research findings are not fully implemented in real-world practice. They typically emerge in applied studies.

Example: AI usage in learning research without providing implementation plans.

The research on AI usage in learning is focused here. We find numerous AI researchers cite benefits, but without actionable classroom strategies. This misalignment prohibits teachers from easily embracing innovations. Bridging this gap guarantees research translates into useful applications, helping educators apply AI tools to enhance learning outcomes and teaching effectiveness.

It occurs when required data is absent, out-of-date, or inadequate. Imperative for empirical studies and analysis.

Illustration: Lack of quality longitudinal data on rural climate adaptation strategies.

For Instance long-term records of rural communities' adaptation to climate change that are few and far between, and thus the assessment of changing trends or the evaluation of the impact of adaptive measures becomes hard. Filling these data gaps by means of systematic data collection and continuous monitoring opens up the possibilities for evidence-based policymaking, informed decisions, and effective interventions that not only support but also strengthen the resilience and sustainability of the communities against the challenges posed by climate change.

Established when current research is contradictory or incomplete. Useful for systematic research.

Example: Contradictory studies of the impact of exercise on stress relief.

Current research yields conflicting findings about the effects of exercise on stress. Some find substantial advantages, others small or sporadic effects. Filling this gap with more controlled, rigorous, or meta-analytic studies can elucidate the connection and inform successful health and wellness initiatives.

Emergencies arise when central concepts are vaguely defined or unevenly applied. Useful for cleaning up terminology.

Example: Vagueness of "sustainable entrepreneurship" worldwide.

The term sustainable entrepreneurship is not definitively defined across the world. Environmental objectives are emphasised by some, social influence or economic sustainability by others. Cultural and geographical variables further obscure its meaning, and selective usage by companies introduces uncertainty. This vagueness in concept serves to prevent comparison, generalisation, and successful implementation, and thus the demands of sharper definitions and models.

It occurs when research in one geographical area overlooks the context in other places. Applicable for comparative studies.

Example: Studies of city hospitals without urban clinics.

Restricted research on large city hospitals disregards issues encountered by smaller urban or rural clinics. Regional variances in resources, patient populations, and infrastructure impact outcomes. Filling these gaps enables comparative studies, broadens applicability, and informs policies enhancing healthcare in varied contexts.

Arise when people or phenomena are not examined over sufficient time frames. Most useful for longitudinal research.

Example: No longitudinal research on remote learning outcomes following a pandemic for years.

Most studies look at short-term remote learning effects but do not follow long-term effects. Following long-term outcomes helps teachers and policymakers improve instructional designs, increase engagement, and reduce learning loss in protracted remote or hybrid learning settings.

It occurs when studies omit policy, legal, or regulatory factors. Essential for policy-guided research.

Example: Insufficient regard for AI adoption and data protection law worldwide.

The research on AI adoption and data protection law worldwide is focused. Regulatory requirements are overlooked in AI research, posing risks in terms of privacy and compliance. Integrating global legal frameworks will make adoption methods ethical, secure, and legally sound. Filling this gap assists organisations with the safe implementation of AI solutions while adhering to worldwide data protection and privacy guidelines.

Research gap identification is vital to making your work original, applicable, and influential.

Adding to originality: Emphasis on less-studied subjects

Informing research design: Helps set up clearly specified research goals

Inform practice and policy: Adds to practical issue-solving in the world

Maximising resources: Prevents wasteful duplication of research effort

Maximising publication potential: Gaps-based research is publishable in high-impact factor journals

Understanding where knowledge is lacking in your field is important for impactful research. Identifying these gaps allows you to focus on unexplored areas, address unresolved questions, and make meaningful contributions to both theory and practice.

Carefully reviewing existing studies in your field helps uncover inconsistencies, unanswered questions, or underexplored areas, revealing potential research gaps for further studies or future investigation.

Examining citation patterns identifies studies that receive minimal follow-up research, highlighting underexplored topics with opportunities for meaningful contribution.

Aggregating results from multiple studies exposes missing evidence, contradictions, and under-researched areas, enabling researchers to address significant gaps.

Collaborating with experienced professionals provides insights into emerging topics, practical challenges, and overlooked areas that require further academic exploration.

Reviewing conference proceedings uncovers recent studies, debates, and emerging topics that have not yet been extensively researched.

Using bibliometric tools and academic databases helps identify subjects studied less frequently, highlighting gaps suitable for a new research focus.

Analysing available datasets reveals missing variables, incomplete information, or underrepresented populations. Such gaps provide opportunities for original research contributions.

Every identified gap is worth pursuing. Prioritise based on three key factors:

Relevance: Ensure the research gap aligns with your field and addresses the current academic or practical need of the study.

Feasibility: Assess whether you have the time, resources, and expertise to conduct the study effectively.

Impact: Get along with the gaps which can advance theory, improve practice or influence policy in a meaningful manner.

Strategic research guidance helps balance these factors and focus your research methodology on areas with the greatest potential contribution.

Even experienced researchers can make errors when pinpointing gaps in existing literature. These mistakes often lead to studies that lack depth, originality, or practical value. Understanding these pitfalls helps ensure your research focuses on meaningful, achievable, and impactful questions. Some of the most frequent errors include:

Addressing too small questions rather than the seminal gaps

Swamping new literature and basing it solely on earlier sources

Overestimating feasibility in the absence of resources and expertise

Neglecting development in research methods

Overlooking research's pragmatic usefulness

A systematic process ensures your research gaps are accurate and well-defined, and you may seek expert research guidance or professional research services to support you throughout the process.

Identifying a research gap is the foundation of producing focused, high-impact research. Through a careful literature review, consultation with experts, and systematic gap ranking, you can uncover meaningful areas worth exploring. Recognising these gaps not only strengthens your proposal but also ensures your work contributes genuine value to your field.

If you’re struggling to identify meaningful research gaps, you can connect with professional PhD guides or experts who can help you strengthen your research, refine your project, and ensure your work meets academic standards with confidence.

Master the top methods of primary data collection in research methodology. Learn to use surveys, interviews, and experiments to gather original, high-quality data.

Don’t write your methodology without reading this. Learn why purposive sampling is essential for case studies and how to define your inclusion criteria. Url:purposive-sampling

Master the chapterization of thesis to ensure logical flow. Learn the standard academic framework for organizing research into a professional, approved document.

A practical guide to sentiment analysis research papers covering methodologies, datasets, evaluation metrics, research gaps, and publication strategies.

Master data analysis for research papers. Learn quantitative and qualitative methods, cleaning, and reporting standards to ensure your study meets journal rigour.

Want to impress your peers? Discover the best ways to condense your research, avoid common mistakes, and handle tough questions at any academic conference.