Katy Richard.K

Do you know that nearly three out of every ten research proposal submissions are declined due to weak or poorly constructed literature reviews? Surprisingly, in many of these cases, it isn’t the research idea itself. Instead, the proposal collapses because it is built on an unstable foundation, outdated, irrelevant, or questionable sources.

Think of the sources of literature review in research as the skeleton of your proposal or thesis. Just as a building needs a strong framework, your study requires reliable sources to prove that it is grounded in evidence.

A literature review is not meant to be a simple list of books and articles stitched together. To be effective, it requires critical thinking, analytical judgment, and the ability to position your own study within a larger scholarly dialogue.

This blog breaks down everything you need to know about sources of literature review in research, what they are, the types you should use, how to find them, how to check their credibility, and practical tips for managing them effectively.

Fundamentally, sources are the raw data that offer evidence, context, and justification for your research. They may be journal articles, books, government reports, datasets, or conference papers.

It's a good idea to think of them in two broad groups:

Information sources – general items such as reports or articles that assist in building up knowledge.

Reference sources – specialist aids such as encyclopaedias or handbooks for fact-checking or clarification.

Not all published work, though, is credible. For example, a peer-reviewed article in The Lancet carries much more significance than an unsubstantiated blog post. The ability to discern between credible and non-credible sources is important because your review is only as powerful as the sources on which it stands.

Researchers typically use three types of sources, each with a specific function in your literature review.

These are original studies or first-hand accounts. They can be raw survey data, journal articles detailing new experiments, or dissertations.

Strengths: Provide original findings and detailed data.

Weaknesses: Highly technical and time-consuming.

Example: A study in The New England Journal of Medicine on new vaccine results from a clinical trial.

These analyse or interpret primary studies. Common examples are meta-analyses, commentaries, or review articles.

Strengths: Summarise trends and offer broader perspectives.

Weaknesses: Potential for author bias or selective reporting.

Example: A meta-analysis of online learning outcomes in Educational Research Review.

These are materials written in a reference style, such as encyclopaedias, dictionaries, or bibliographies.

Strengths: Useful for background information.

Weaknesses: Not very detailed and hardly ever classed as strong academic evidence.

Example: A psychology textbook on theories of cognitive development.

The ideal reviews integrate all three. Utilise primary studies for depth, secondary sources for synthesis, and tertiary ones for context.

One of the biggest challenges is where to look. Good research material is dispersed across various platforms, and access relies on institutional subscriptions.

Here are the most typical sources:

Multidisciplinary Databases: Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar.

Subject-Specific Databases: PubMed (medicine), IEEE Xplore (engineering), PsycINFO (psychology), JSTOR (humanities).

Grey Literature: Government reports, policy papers, white papers, doctoral theses are excellent sources but frequently ignored.

University Libraries: A treasure trove of subscription-based publications and tools.

Mastering how to navigate these areas quickly will save you hours and mean that your review is grounded in robust evidence.

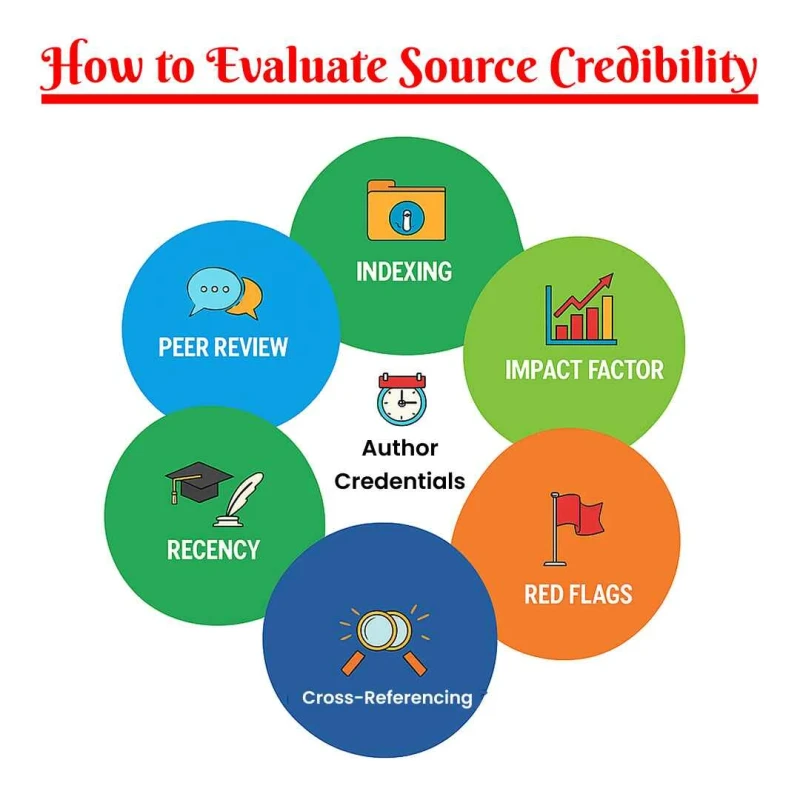

With so much information available on the web and the increased application of AI to literature review resources, it is simple to be distracted by material that appears to be credible but has no academic substance.

Here is a brief checklist for assessing credibility:

Peer Review: Was the work peer-reviewed?

Indexing: Is the journal listed in Scopus, Web of Science, or PubMed?

Impact Factor: Greater numbers tend to signify greater influence.

Recency: Put the most recent five years at the top in rapidly evolving areas, and a decade at most in slow-moving fields.

Author Credentials: Is the author a scholar of standing?

Cross-Referencing: Is it being cited by other well-respected works?

Red Flags: Steer clear of predatory journals, unvetted blogs, and unverifiable open-access sources.

Being selective lends not just credibility to your review but to your entire study.

Not all sources are equal. A simple three-tier system assists you in making your priority-listing decisions:

Tier 1: Peer-reviewed journals, scholarly monographs, conference papers.

Tier 2: Review articles, encyclopaedias, subject dictionaries.

Tier 3: Blogs, general websites, unchecked material.

Use a simple chart to see which sources make up the bulk of your review and which are still supplementary.

Good literature reviews have breadth (coverage of the field at large) and depth (analysis of the most pertinent studies) in the right balance.

Some strategies:

Broad to Narrow Approach: Start with review articles prior to focusing on individual studies.

Boolean Operators: Apply AND, OR, NOT while searching databases to narrow down results.

Set Alerts: Google Scholar Alerts can inform you of new papers in your area of interest.

Ratio Guideline: Target approximately 70% primary, 20% secondary, and 10% tertiary sources.

Having the correct sources is only half the job. Organising them facilitates a smooth writing process.

Use citation managers such as EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley.

Develop an annotated bibliography ahead of time to monitor why each source is important.

Mark and group by topic, method, or timeline.

Maintain a well-organised folder system for PDFs and notes.

Good organisation avoids last-minute desperation and helps your writing make sense.

Even seasoned researchers get caught out. Some of the most frequent missteps are:

Too much dependence on tertiary sources such as textbooks.

Stuffing reviews with meaningless content solely for the purpose of making them longer.

Citing old studies without apology.

Quoting secondary reviews exclusively without verifying original studies.

By avoiding these errors, your credibility is immediately enhanced.

The sheer amount of information available can be daunting. Factor in the threat of predatory publishers and the intricacies of subscription-based databases, and it's no wonder many researchers find themselves at a loss.

Efficiently locate genuine, quality sources.

Help avoid low-impact or dubious journals.

Provide access to resources behind paywalls.

Increase your chances of proposal approval or journal acceptance.

At Ondezx, we’ve worked with countless researchers to build strong, credible literature reviews that impress reviewers and committees alike.

Ultimately, how good your literature review is all rests on your choice of sources of literature review in research. Strong, up-to-date, and well-balanced sources provide your research with a robust foundation, whereas poor ones may lead to rejection.

Emphasise quality over quantity. Employ a proper combination of primary, secondary, and tertiary sources, use strict criteria of evaluation, and remain well-organised during the process.

And remember, you don’t have to go through it alone. If you want expert support in building a powerful literature review, Ondezx is here to guide you and help bring your research one step closer to success.

Data Analysis in a Research Paper: How We Apply Methods and Reporting Standards

How to Present a Paper in a Conference – A Complete Academic Guide

Problem Identification in Marketing Research: Methodologies, Sources, and Analytical Approaches

How to Write References in a Research Paper with Proper Formatting and Journal-Level Accuracy

Research Problems Ideas – A Practical Guide to Identifying, Framing, and Refining Strong Research Topics